Kiki Smith, Born, 2002, Bronze.

Kiki Smith investigates the human experience and draws from a variety of artistic expressions. “Since she emerged in the early 1980s, Smith has been a fascinating and inventive presence. Her provocative meditations on the human body and the realms of myth, spirituality, nature, and narrative have resulted in works of extraordinary power and uncommon beauty.” (1) Smith’s practice also references her extensive knowledge of art history but instead of using the female form as the subject of her art, she uses the feminine as the object. The body is a “receptacle for knowledge, belief, and storytelling.” (2) In the 1990s Smith began engaging with feminine archetypes, from the biblical through to cultural mythology and fairy tales. (3) Unlike her predecessors, Smith weaves these stories together and invites new narratives & interpretations. (4)

Kiki Smith, Lilith, 1994, Bronze with glass eyes, 80 cm x 68 cm x 44 cm

At The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

At The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Smith’s bronze sculpture, Lilith 1994, was cast from a live model that crouched on the floor. Lilith was Adam’s first wife, but she infamously abandoned him and ran away to the Garden of Eden. Lilith refused to submit to a subordinate role and is therefore considered a symbol of feminine strength. (5) But according to Hebrew lore, Lilith is depicted as a night demon. Smith converges these narratives and displays the sculpture upside down clinging to the wall, her glass eyes eerily peer down at the viewer. (6)

Glass Eyes.

Kiki Smith, Pietà, 1999, Printer’s ink, ink and graphite on joined paper, 140 cm × 77 cm

Kiki Smith, Pietà, 1999, Printer’s ink, ink and graphite on joined paper, 140 cm × 77 cm

Smith’s Pieta drawings depict the grieving artist cradling her dead cat. The intimate self-portraits mimic the history and traditions of the Pieta in both title and composition. (7) The drawings further explore Smith’s resounding themes of human experience: death and the fragility of life.

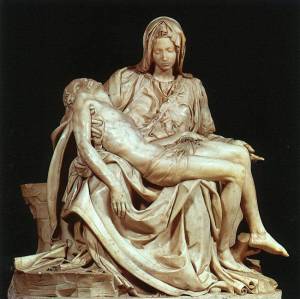

Michelangelo, Pietà, 1498–1499, Marble, 174 cm X 195 cm

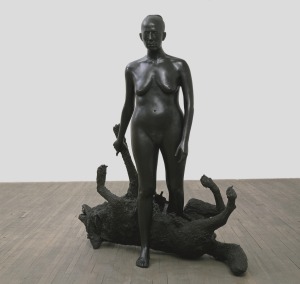

Smith uses fairy tales like, Little Red Riding Hood, as a metaphor to express her perturbed feelings about the feminist experience in patriarchal culture. (8) Smith’s monumental sculpture, Rapture 2001 depicts the macabre scene when the woodcutter saves the grandmother and the young girl from the wolf. Yet, a life-sized woman steps out of the stomach of a dead wolf that is lying on its back in Smith’s bronze sculpture. Smith explores the idea that the tale is inherently violent and that critics have interpreted it as a symbolic parable of rape. (9) On Smith’s work Langer writes, “The challenge here is not to make bad literary picture but rather to create counter-narratives that are dramatic, sometimes reckless, many times vulgar, and above all strange. These images are self-consciously primitive with their swelling contours, violent, intensely personal touches of color, and successive layers of strokes and lines cutting into the surface.” (10)

Kiki Smith, Rapture, 2001, Bronze,

References

1. Walker Art Center, Collections > Kiki Smith, accessed 15 March 2013 <http://www.walkerart.org/collections/artists/kiki-smith>

2. PBS, Art in the Twenty-First Century, accessed 15 March 2013, <http://www.pbs.org/art21/artists/smith/index.html>

3. Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc., 2005, Kiki Smith: A Gathering, 1980-2005, accessed 15 March 2013, <http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/6aa/6aa177.htm>

4. ibid., p. 8.

5. ibid., p. 4 & 7.

6. ibid., p. 7.

7. ibid., p. 9.

8. C Langer, review of W Weitzman’s ‘Kiki Smith: Prints, Books & Things’, Woman Art Journal Vol. 26, No.2 (Autumn, 2005 – Winter, 2006)

9. Bonner S, Visualising Little Red Riding Hood, London’s Global University, 2009.

10. Langer, op. cit., p. 56.

Images

Born <http://art160sxu.blogspot.com.au/2010/04/kiki-smiths-born.html>

Lilith <http://blog.sfmoma.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/lilithone.jpg>

Lilith <http://farm8.staticflickr.com/7156/6613911795_4f2007f542_z.jpg>

Lilith <http://farm3.staticflickr.com/2176/2445591969_952ec4974a.jpg>

Pieta <http://whitney.org/image_columns/0004/8838/2001.151_smith_imageprimacy_compressed_600.jpg>

Rapture <http://24.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_ly9a5fTvxW1qbo39mo1_1280.jpg>