After World War II, a sense of optimism prevailed as the United States and Britain enjoyed a remarkable period of economic and political growth. (1) Middle class Americans moved into affordable, mass-produced homes in the suburbs and television became more popular than radio. Mass communication began to saturate homes in the industrialized world. (2)

In Britain, by the late 1950s and early 1960s, artists and thinkers began to rebel against a dull and stifling world bound by social conformity. Looking to the United States, these artists saw “a more inclusive youth culture that embraced the social influence of mass media and mass production.” (3)

Inevitably, a cultural revolution gained momentum, as mass media streamed major events into living rooms around the world. Pop art emerged during the turbulent times of the Vietnam War and the protests it incited, the Civil Rights Movement and its call for equality of African Americans and the women’s liberation movement. (4)

Pop artist’s based “their techniques, style, and imagery on certain aspects of mass reproduction, the media, and consumer society, these artists took inspiration from advertising, pulp magazines, billboards, movies, television, comic strips, and shop windows. These images, presented with (and sometimes transformed by) humor, wit, and irony, can be seen as both a celebration and a critique of popular culture.” (5)

Richard Hamilton’s compelling collage of 1956, Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?, is crammed with all the new consumer products from the United States. On the surface it is a playful and naïve work, however, as Fiona MacCarthy writes, “at a more profound level it is horribly disquieting. No other work of art of its period expresses so precisely the jarringly ambivalent spirit.” (6) Hamilton’s disdain towards the dominance of America’s consumer culture is abundantly clear in his work.

Richard Hamilton, Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? 1956.

Andy Warhol saw American society as a world of ready-mades. He once famously wrote, “All cokes are the same, and all cokes are good.” (7)

Andy Warhol, Green Coca-Cola Bottles, 1962.

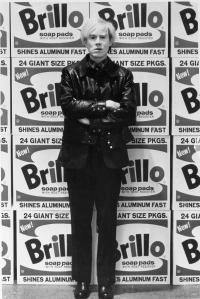

Warhol liberated the art world and attitudes towards art radically shifted. It was the ideas behind Warhol’s art that makes him significant. Warhol was saying that Twentieth century America is about this, it is about movie stars, Brillo boxes, Coca-Cola and Campbell’s soup. His art dealer Ivar Karp said, “In this thing orientated world, Andy was a kind of God. America is a thing orientated culture, it’s a culture of objects and we bow down to that God everyday. Andy produced the artifacts. Andy gave us what we bow down to, things, movie stars, boxes, the American dream and life and finally death.” (8)

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962.

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962.

Andy Warhol poses with his series of prints titled The Brillo Boxes at the Tate Gallery in London on February 15, 1971.

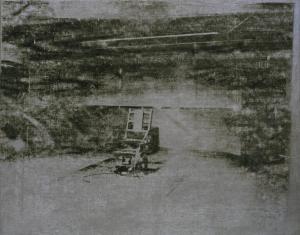

Warhol’s images are contrary to the heroic images of the Abstract Expressionists. On the surface there is a sense of buoyancy and optimism in Warhol’s work. It is glossy and bright, like the products that line supermarket shelves. However, there is also an unsettling quality. For instance, Warhol used a newspaper image of an empty electric chair in 1963 and returned to the subject of the death penalty for the next decade. A disturbing metaphor for death, “the chair, and its brutal reduction of life to nothingness, is given a typically deadpan presentation by Warhol.” (9)

Andy Warhol, Electric Chair, 1964.

In the aftermath of John F Kennedy’s assassination, Warhol scoured newspapers and magazines for images of his wife, Jackie Kennedy. Warhol used eight photographs in his series ranging from Jackie arriving in Dallas to attending her husband’s funeral three days later. Warhol said that what bothered him the most was the way the media was “programming everybody to feel so sad.” (10) Echoing his sentiments, Alastair Sooke writes, “The serial nature of the Jackie portraits – the way the images are repeated over and over again – is a metaphor for how the news media can work: bludgeoning its audience with a finite set of pictures and words, until we are “programmed” to think and feel a certain way.” (11)

Andy Warhol, Jackie Kennedy, 1963.

References

1. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/pop-art

2. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/pop-art

3. http://www.slideshare.net/jackjsargent/pop-art-photographers

4. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/pop-art

5. http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/movements/195228

7. http://en.m.wikiquote.org/wiki/Andy_Warhol

8. Andy Warhol A Documentary http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0862644/

9. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/warhol-electric-chair-t07145

10. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140418-jackie-warhols-pop-saint

11. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140418-jackie-warhols-pop-saint

Images

Richard Hamilton, Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? 1956. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/feb/07/richard-hamilton-called-him-daddy-pop

Andy Warhol, Green Coca-Cola Bottles, 1962. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Coca-Cola_Bottles

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marilyn_Diptych

Andy Warhol poses with his series of prints titled The Brillo Boxes at the Tate Gallery in London on February 15, 1971. http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/remembering-life-legacy-andy-warhol-gallery-1.1893857?pmSlide=1.1893846

Andy Warhol, Electric Chair, 1964. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/warhol-electric-chair-t07145

Andy Warhol, Jackie Kennedy, 1963. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140418-jackie-warhols-pop-saint

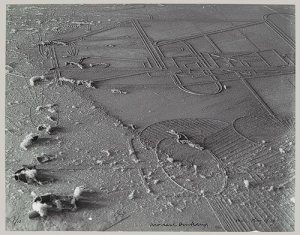

Otto Umbehr, Mystery of the Street, 1928.

Otto Umbehr, Mystery of the Street, 1928.