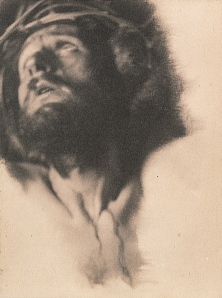

Postmortem photograph of unidentified child. Harrison, Lock Heaven, Pa., ca. 1890-1910. Tinted gelatin silver print on cardboard mount, carte de visite. Courtesy, Center for Visual Communication, Mifflintown, Pa.

The enduring tradition of painted mortuary portraits precedes Nineteenth century mortuary photography. Jay Ruby writes, “The association of death and sleep is as old as Western culture itself. In classical Greece, the sons of the night were Hypnos, god of sleep, and his twin, Thanatos, god of death.” (1)

The denial of death was a pictorial convention that prevailed during the Nineteenth century. “People did not die. They went to sleep.” (2) The “last sleep” was a popular theme in mortuary photography because it beautified death by creating the illusion of sleep. With the high infant mortality rates during this time, mourning was a normal part of life. Memorialising the deceased was common and mortuary photographs were often displayed in the home.

A photograph retained the memory of the deceased and was also a lasting reminder that we have no power over death, a memento mori. The young boy (pictured above) is dressed in his Sunday best and it was probably the first and last time he was photographed. The photographer has adhered to the prevailing ideology of the day, and the boy appears to be sleeping. The photograph is a carte de visite, a small photograph that was relatively inexpensive to produce. The carte de visite was hugely popular and people would collect, trade or send them to loved ones. I cannot help asking whether his mother still carried him, even after his death, in her pocket.

References

1. J Ruby, Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America, Twelvetrees Press, 1990, p. 63.

2. ibid.

Image

J Ruby, Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America, Twelvetrees Press, 1990, p. 66.