Inta Ruka (1958-present) is one of the major figures in the fine art, documentary photography in Latvia since the early 1980s when Latvia was still under Soviet occupation until the present. Latvia regained independence in 1991, after being illegally annexed by the Soviet Union under the provisions of the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany and its Secret Additional Protocol of August 1939. In the early 1980’s a ‘new wave’ (1) of Latvian photographers used subjective documentary photography to challenge Soviet ideology, Soviet Socialist Realism and the decorative and simplistic ‘established pictorial aesthetics of [Soviet-Latvian] camera clubs.’ (2) At the same time, the supposed truthfulness of documentary photography was compatible with the rhetoric of glasnost―openness, directness and transparency. (3) These photographers not only set new aesthetic and critical standards by raising photography to a fine art status (that was still excluded from the accepted visual arts discipline which consisted of painting, graphic arts and sculpture) which was inspiring, contemplative and sophisticated, but also engaged in dialogue. This work was characterised by its subjective documentary nature, by the ‘straight’ un-manipulated black and white photographs and its apparent directness and honesty as well as by the Latvian experience.

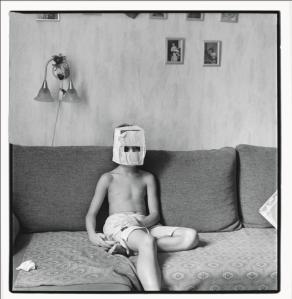

Ruka is distinguished by her well known series My Country People (ca. 1983 – 2000) and People I Happened to Meet (1988, 2000-2004), where she initiates up conversations with strangers and then, by mutual consent, photographs them. In the series Amalijas Street 5A (2004-2008), she portrays the residents of an old Rigan wooden apartment block not only recording their faces/spaces and histories via short commentaries, but also provides a startling/disquieting view of the socio-economic situation in Latvia since its integration into the European Union. In short, this series addresses the dichotomies of life―happiness/sadness and love/hate.

‘Richards Stibelis’, 2006, from Amalijas Street 5A, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka

My Country People consists of portraits of people from Balvi, a rural area in Latvia from which her mother originates and where she spent many summers of her childhood. (4) Old women, men and children are photographed in their domestic settings—places in which they feel simultaneously ‘organically bound’ and ‘free.’ (5) Likewise, the photographs are characterised by the way the subject directly confronts the camera. Apparently, the subjects strike their own pose. (6) Whatever the complicity apparent between the photographer and the photographed, the ease in which the subject has posed and the trust s/he has in Ruka are confirmed by the pictures themselves as they later will be found hanging in their homes. (7)

‘Iveta Tavari, Edgars Tavars’, 1987, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka

My Country People challenges Soviet iconography of peasant life, stereotypical poses of healthy workers in the field as model citizens. Ruka’s defiance, however, is by no means overt criticism of the regime or the reason behind the work. Although Estonian photographer and critic, Peeter Linnap, regards her selection of subject matter as being based on a romantic point of view that is ‘elusive and enigmatic’, Ruka’s motivation is, as Canadian photographer, Vid Ingelevics, suggests, more straightforward. (8) On the one hand, it indicates a symbolic return to her roots and childhood as she pays homage to her past. On the other hand, it signifies, as German art historian, Barbara Straka suggests, ‘remembering and mourning [and] its irretrievability.’ (9) In short, Ruka confronts, as Swedish art critic, Ute Eskildsen suggests an ‘old and vanishing world.’ (10) In his essay ‘Mourning and Melancholia’, Austrian psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud, argues the strength of attachment to the lost person/abstraction determines the length of time of mourning. Overcoming it is often a long process because ‘people never willingly abandon a libidinal position’, physically prolonging the ‘existence of the lost object.’ (11) Freud finally assures his readers that the mourners overcome their grief ‘after a certain lapse of time.’ (12) Additionally, I would argue that Ruka’s return to wonders of childhood aligns with the wonderment connected to the invention of photography, as well as German philosopher, Ernst Bloch’s concern for Heimat—the familiarity and safeness of feeling at home. Likewise, the concept of wonder, that was significant for Bloch, which describes Ruka’s feelings for people and nature and conveys their enigmatic qualities. This parallels Bloch’s use of the German word for wonder (Staunen) which Jack Zipes translates as: ‘intended to startle us in a mysterious and mystical sense . . . not only startlement but astonishment, wonder, and staring.’ (13)

Untitled (Ruka with her models), ca.1984, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka

In keeping with Bloch’s philosophy on human dignity, Ruka portrays her subjects with the utmost sincerity, respect and dignity. (14) She photographs people in their private space (as opposed to collective) and attempts to uncover the essence of their human character. The square format, that undermines the horizontal purview of human vision, and the conventional eye-level vantage point, appears confrontational but is countered by Ruka’s sensibility and simplicity. Ruka does not alienate her subjects but rather unites them. She also urges the viewer to consider the values of quality human relationships. She identifies with the people and further links herself to the land by cycling around Balvi each summer carrying her old 1950’s Rolleiflex and tripod. (15) Although her work is premeditated and directorial, the end result is, as Latvian photographer, Andrejs Grants suggests, ‘organic and unforced.’ (16)

Several critics draw parallels between Ruka’s work and August Sander’s Man of the Twentieth Century project (1929)—a series of portraits intended to draw attention to the social and cultural dimensions of life in Weimar Germany. (17) Ruka herself admits that her first encounter with Sander’s work made a vivid impression on her. (18) For example, in his essay entitled ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka’, Linnap notes that both photographers stage their documentaries and identifies their work as an ‘artistic survey catalogue.’ (19) Sander’s anthropological methodology identifies the sitters and their physiognomy according to labels and trades/professions—Peasant Bride, Young Mother, Small-Town People, Bourgeois, Bohemians, Industrialist, Judges and Lawyers etc.—endowing his studies with a clinical detached gaze. While Sander’s work can be criticised for its stereotyping of people and monologic encounters, Ruka’s work engages dialogue that is in accord with Russian literature theorist, Mikhail Bakhtin’s call for dialogue. (20)

Following Bloch’s humanist and exploratory approach, Ruka instinctively pursues utopian impulses and attempts to discover the world in people and the people in the world. (21) She seems to be more interested in people, as Linnap suggests, as ‘archetypes, as particular expressions of the wealth of humanity.’ (22) In his essay ‘Art and Utopia’, Bloch distinguishes certain features that supplement the status quo in an anticipatory countermove ‘against the Bad Existence’ that is not deceitful or merely embellishment. (23) He writes: ‘When they refer mostly to concentration, they are known as archetypes, when they refer mostly to perfection they are known as ideals; when they refer mostly to meaning they are known as allegories and symbols.’ (24) These structural categories are subject to the utopian function and anticipatory illumination and, as in Ruka’s case, it awakens one to ‘cultural heritage . . . the knowledge of what is missing.’ (25) She keeps Bloch’s ‘promise of culture, which means building its house.’ (26) Separating ‘utopia from ideology’, Ruka’s photographs remain open-ended. (27)

Naming each subject identifies her sitters and signifies respect. (28) In a recent publication, Ruka ‘adds descriptions or quotes that give a sketch of the encounter with or experience of the subject.’ (29) For example, next to the portrait of Vladimirs Pušpurs (1984), she writes:

Vladimirs works a lot and jokes a lot. There is no job he couldn’t do. He grows his own tobacco and has created his own tool for cutting it. Likewise he made a butter churning device. Vladimirs plays the violin. Often after supper, around midnight, the whole family play and sing, after a hard day’s work on the farm. (30)

Unlike Sander, Ruka’s vernacular is romantic and her gaze is compassionate. At the same time Sander’s typology and Ruka’s archetypes illustrate Bloch’s notion of nonsynchronism—the simultaneous coexistence of types (of experience, class, qualities) in the present that belong to past moments of history. (31) Polish photographer Zofia Rydet’s series entitled ‘Sociological Record’ (1978-1986), illustrates the dying lifestyle of Polish peasants, that also demonstrates Bloch’s nonsynchronisation. But Ruka refuses the notions of anthropology and ethnography to locate her work although she admits that certain traditions and ways of life are fast disappearing. (32) Grants also considers ethnography a genre to avoid because it presents boundaries of confine. He terms the ‘scene of the real actor’ where the photographer takes pictures, more characteristic of the time and place. (33) Nonetheless, the social survey or mapping nature apparent in Sander and Ruka’s work gets entangled in contemporary evaluations in which aesthetic and historical experiences can be, as American theorist, Alan Sekula, observes, interchanged and recontextualised—an issue that needs addressing. (34)

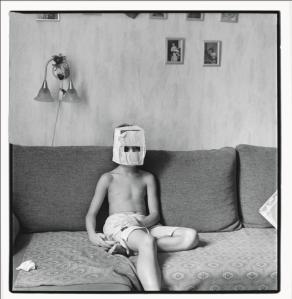

Fundamental to Ruka’s portraiture is her concern with formal qualities—texture, rhythm, light, proportion and movement—that are imbued, as Linnap observes, with a ‘purposeful significance.’ (35) She only uses available light. Her photographs of young children convey an optimistic view of childhood, combining expectation, curiosity, playfulness and entertaining qualities associated with fairy tales. Like the readers of Bloch’s ‘Better Castles in the Sky at the Country Fair and Circus’ who become part of the fantasy imagery, encountering fragments of plots, catalogues of types and figures, arrays of historical and generic categories, Ruka’s subjects live out their fantasies. (36) For example, a sharply focused photograph of a young boy facing the camera with one hand covering his eyes alludes to a game, a prayer or a wish.

‘Agita Rutkaste’, 1984 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Another small boy standing further back, who is out of focus and faces the camera left, has his eyes closed and holds his hands as if in prayer. The two figures are located in an empty room and together they form a triangle within the square, contrasting to the vertical movement of the walls and the diagonal movement of the floorboards. In contrast to the vagaries of life, Ruka positively exposes new dimensions through the power of the imagination which helps build one’s inner resources. A photograph entitled ‘The Girl’, 1992, which shows a girl with long blonde hair wearing a light coloured short sleeved dress that reaches down to her knees, can be likened to American photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s photograph of his daughter who is captured in the act of spinning around (1965). (37)

‘The Girl, Balvi, Latvia’, 1992 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka,

Both girls occupy the centre of the image and are similar in age, appearance and dress. Just as Bloch, who in the midst of his fairy tale surveys, abruptly interrupts the text to remind the reader that ‘the fairy tale does not presume to be a substitute for action’, the two figures counterbalance and contrast to the dark, rough textured wooden shed in the background. (38) Anchored by opaqueness, the utopian quest is suddenly illuminated through the blurry movement—in Meatyard’s image through the twirling movement and in Ruka’s through the blurry movement of the leaves of the tree and the dress—and by the happy smiles.

Ruka’s subjects are rooted in the home environment—their clothes, their personal belongings and paraphernalia. The photograph of the old couple in their simple house—with a bare light globe, tar papered walls, floorboards, single beds and a cupboard with an old-fashioned television—not only exemplifies a lifestyle without unessential material goods, but also shows them as appearing comfortable and content.

‘Emma Stebere and Jânis Stebers, Balvi, Latvia’, 1984 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

With a hand on her hip and a dishcloth in the other hand, the barefooted woman has her back to the viewer and seems absorbed in her programme. The old man sits on the bed equally fascinated. Apart from her formalist and aesthetic concerns, Ruka apparently comments on non-competitiveness, satisfaction and the simple things in life.

While Sanders was interested in gestures that he thought had social implications, Ruka addresses more meaningful issues such as culture, mortality, existentialism, family, procreation and nature. For example, a sharp three-quarter photograph of a tired looking man sitting on the edge of a metal bed contrasts to the tiny baby lying in the bed.

‘Inese Rutkaste, Imants Rutkaste’, Balvi, Latvia’, 1985 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Likewise, the blurry movement of the baby’s arms contrasts to the man’s resigned, clasped hands. It is as if the photographer has pictured the circuitous journey of life. Additionally, the side-lighting casts an ambiguous shadow on the wall and the viewer cannot be sure whose shadow it is—the man’s or the photographer’s? Ruka’s portrait of a mother wearing a big Jānis wreath of leaves and grass on her head and her two children—her son also wearing a wreath—fuses nature and culture.

‘Edgars, Iveta, Daina Tavari’, Balvi, Latvia’, 1986 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka

Contrary to Latvian tradition, the faces are visible under the abundance of greenery—the young boy looks wistful, the mother looks kind and serene, and the young girl shyly responds to the camera with a half smile. In her description of Ruka’s work, critic Jane Richards suggests Ruka’s subjects are like those of Sanders because they are nameless and stand before the camera ‘lost and confused.’ (39) I would argue that Richards’ criticism closes her off from Ruka’s compassionate gaze and cultural understanding.

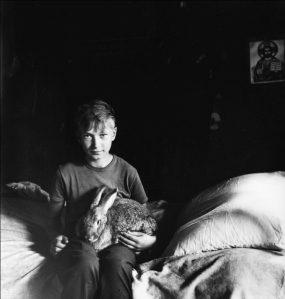

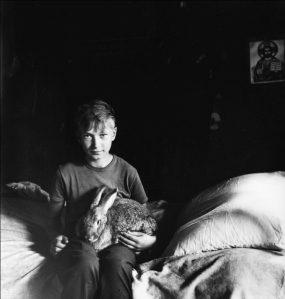

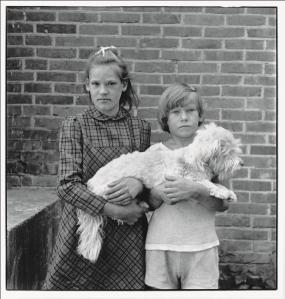

Ruka also photographs people with their animals—a young girl holding her dog, two girls holding a big dog, an old woman holding her dog, an old woman sitting on the bed with her cat, and a male hunter with his dog. Unlike American photographer, Garry Winogrand’s, poignant portrait of a man holding his rabbit which expresses sadness and defeat, Ruka’s portrait of a young boy sitting on a bed holding his fat rabbit conveys warmth and hope. (40)

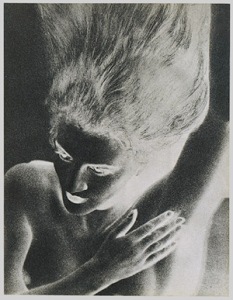

Untitled (Boy and his rabbit), ca.1984, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

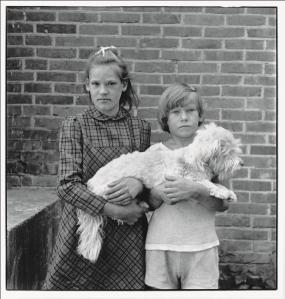

The relaxed rabbit sits comfortably and looks content and familiar in the surroundings. The boy’s love and devotion to his pet rabbit conveys the notion of hope. Likewise, Winogrand’s portrait of a fat lamb and fat boy (ca.1974-1977), again illustrating fall and decline, also demonstrates both the photographer’s and the subject’s ennui—their boredom, inactivity and tired-of-life attitude. (41) While Winogrand illustrates banality, Ruka depicts a caring and relaxed relationship between subject and animal. Although the situation sometimes appears humorous—for instance, two young girls embrace a huge shaggy haired dog in their arms as if it is a baby—Ruka averts banality through her sense of responsibility.

‘Agita Rutkaste, Andis Rutkaste’, 1992, silver gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

It may be argued that like American writer, James Agee and American photographer, Walker Evans in their project Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), Ruka exploits private moments for her own private gain. (42) By identifying the sitters, she locates a place in the archive for the people in the national collective memory, providing a new framework from which new histories can be told. German historian Siegfried Kracauer’s warning that to possess the historical subject is to lose it, recasts Ruka’s project in historical terms. (43) Yet she does not try to recover these people for history. (44) The implicit motive of Ruka’s study—her respect for her roots, the land and the people—does not foreclose historical speculation or social engagement. Rather it discloses the photographer’s honesty about the terms of this transaction, the context that inspired it and the purposes to which it may be put.

Post script. Interestingly enough, Ruka collaborated with Swedish filmmaker Maud Nycander on a documentary film titled ‘Road’s End’ that followed the life of Daina, the protagonist in Ruka’s photograph ‘Edgars, Iveta, Daina Tavari’ and her dog George Bush. It shows Daina thirty years later, still living in the house in Balvi without running water and no electricity. Abandoning the impoverished Latvian countryside, her daughter, Iveta, now lives in Italy while her son, Edgars, lives in Norway.

References

1. Helena Demakova, ‘Group A: Ideals and Reality—The Ideal and Real Space of Group A’, trans. Martinš Zelmenis, Māksla, No. 146, April 1991, Rīga, pp. 56-63.

2. Alise Tifentale, ‘The new wave of photography: The role of documentary photography in Latvian art scene during glasnost era’ https://www.academia.edu/1856067/The_new_wave_of_photography_The_role_of_documentary_photography_in_Latvian_art_scene_during_glasnost_era, p. 4 retrieved 14.5.2014.

3. Documentary photography is not to be confused with photojournalism.

4. According to Barbara Straka and Swedish writer Ute Eskildsen, Ruka began this series in 1983. Andrejs Grants, however, dates it from 1985. Ruka herself remains allusive about dating this series although some of her early work is dated 1984. Photographs, however, included in this series were photographed in the late 1970s. See: Barbara Straka, ‘The Memory of Images: Baltic Photo Art Today’, The Memory of Images: Baltic Photo Art Today, exhibition catalogue, Nieswand Verlag, Stadtgaleries im Sophienhof, Kiel, March 17-April 25, 1993, p. 21; Letter from Andrejs Grants to the author, 15.4.1996; Inta Ruka, People I Know, Ute Eskildsen, trans. Rolli Főlsch, Bokőrlaget Maz Strőm, Stockholm, Sweden, 2012, p. 7.

5. Letter from Andrejs Grants to the author, 15.4.1996.

6. Ruka, People I Know, p. 11.

7. Vid Ingelevics, ‘Introduction’, Latvian Photographers in the Age of Glasnost, exhibition catalogue, Toronto Photographers Workshop, Toronto, May 18-June 22 1991, p. 7.

8. See: Peeter Linnap, ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka: 1980’s: Romantic Catalogue on Latvia’, Borderlands: Contemporary photography from the Baltic States, (ed.) Martha McCulloch, exhibition catalogue, curated by Peeter Linnap with the assistance of Valts Kleins and Gintautas Trimakas, Street Level Photography Gallery and Workshop, ‘The Cottier’, Glasgow, June 5-July 4 1993, n.p; Letter from Vid Ingelvics to the author, 23.8.1996.

9. Straka, ‘The Memory of Images’, p. 21.

10. Ruka, People I Know, p. 8.

11. Sigmund Freud, ‘Mourning and Melancholia’ in On Metapsychology: the theory of psychoanalysis, Vol. 11, trans. James Strachey, (ed.) Angela Richards, The Pelican Freud Library, Penguin Books, London, 1985, pp. 244-245.

12. Charity Scribner, Requiem for Communism, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2005, p. 90.

13. Ernst Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature: Selected Essays, trans. Jack Zipes and Frank Mecklenburg, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1993, p. xxxi.

14. Jan Robert Bloch, ‘How Can We Understand the Bends in the Upright Gait?’, trans. Capers Rubin, New German Critique, No 45. Fall 1988, pp. 9-39; Ernst Bloch, Natural Law and Human Dignity, trans. D. J. Schmidt, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1986.

15. Apparently, when her son was younger she would carry him on her bicycle.

16. Letter from Andrejs Grants to the author, 15.4.1996.

17. Linnap, ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka’, n.p.

18. Ruka, People I Know, p. 8.

19. Linnap, ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka’, n.p.

20. Mikhail Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, (ed.) Michael Holquist, trans. Michael Holquist and Caryl Emerson, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1981.

21. Inta Ruka, ‘My People from the Country’, Parmijas, Contemporary Art from Riga, Münster, 1992, p. 34.

22. Linnap, ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka’, n.p.

23. One of the subheadings of this chapter is entitled ‘The Utopian Function Continued: Its Inner Subject and the Countermove against the Bad Existence’ (Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature: Selected Essays, p. 108).

24. Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature, p. 110.

25. Jack Zipes, ‘ Something’s Missing: A Discussion between Ernst Bloch and Theodor W. Adorno on the Contradictions of Utopian Longing’, 1964 in Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature, pp. 1-17.

26. Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature, p. 58.

27. Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature, p. 58.

28. Naming the subjects Linnap terms as an act of politeness (Linnap, ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka’, n.p).

29. Ruka, People I Know, p. 8.

30. Ruka, People I Know, pp. 8-9.

31. See: George Baker, ‘Photography between Narrativity and Stasis: August Sander, Degeneration, and the Decay of the Portrait’, October, 76, Spring 1996, p. 87; Ernst Bloch, ‘Nonsynchronism and The Obligation to Its Dialectics’, trans. Mark Ritter, New German Critique, No. 11, Spring 1977, pp. 22-38.

32. Artist’s statement June 1998.

33. Letter from Andrejs Grants to the author September 1996.

34. Alan Sekula, ‘Reading an Archive’ in Blasted Allegories, (eds.) Brian Wallace and Marcia Tucker, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1991, p. 123.

35. Linnap, ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka’, n.p.

36. Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature, pp. 167-185.

37. Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled (Girl twirling in front of a shed), 1965, silver gelatin print in An American Visionary, (ed.) Barbara Tannenbaum, Akron Art Museum, Rizzoli, Ohio, 1991, pp. 35-37; Baker Hall, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Aperture, New York, 1974, p. 122.

38. Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature, p. 170.

39. Jane Richards, ‘Freedom Shots’, The Independent, 18.1.1994, p. 24.

40. Garry Winogrand, ‘Fort Worth Texas’, ca.1974-77, silver gelatin print in John Szarkowski, Winogrand: Figments From the Real World, The Museum of Modern Art New York, New York, 1988, p. 187.

41. Garry Winogrand, ‘Fort Worth Texas’, (Lamb and boy), 1975, silver gelatin print in Szarkowski, Winogrand, p. 187.

42. James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Farmers, Ballantine Books, New York, 1966.

43. Siegfried Kracauer, History: The Last Things Before the Last, Markus Wiener Publishers Inc., Princeton, 1995, p. 79.

44. For the recontextualistion of history see Charles Wolfe, ‘Just in Time: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and the Recovery of the Historical Subject’ in Fugitive Images: from photography to video, (ed.) Patrice Petro, Indiana University Press, Indiana, 1995, pp. 196-217.

Bibliography

Agee. James and Evans. Walker, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Farmers, Ballantine Books, New York, 1966.

Baker. George, ‘Photography between Narrativity and Stasis: August Sander, Degeneration, and the Decay of the Portrait’, October, 76, Spring 1996.

Bakhtin. Mikhail, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, (ed.) Michael Holquist, trans. Michael Holquist and Caryl Emerson, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1981.

Demakova. Helena, ‘Group A: Ideals and Reality—The Ideal and Real Space of Group A’, trans. Martinš Zelmenis, Māksla, No. 146, April 1991, Rīga.

Bloch. Ernst, ‘Nonsynchronism and The Obligation to Its Dialectics’, trans. Mark Ritter, New German Critique, No. 11, Spring 1977, pp. 22-38.

Bloch. Ernst, Natural Law and Human Dignity, trans. D. J. Schmidt, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1986.

Bloch. Ernst, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature: Selected Essays, trans. Jack Zipes and Frank Mecklenburg, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1993.

Ernst Bloch, Natural Law and Human Dignity, trans. D. J. Schmidt, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1986.

Bloch. Jan. Robert, ‘How Can We Understand the Bends in the Upright Gait?’, trans. Capers Rubin, New German Critique, No 45. Fall 1988, pp. 9-39.

Freud. Sigmund, ‘Mourning and Melancholia’ in On Metapsychology: the theory of psychoanalysis, Vol. 11, trans. James Strachey, (ed.) Angela Richards, The Pelican Freud Library, Penguin Books, London, 1985.

Hall. Baker, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Aperture, New York, 1974.

Ingelevics. Vid, ‘Introduction’, Latvian Photographers in the Age of Glasnost, exhibition catalogue,Toronto Photographers Workshop, Toronto, May 18-June 22, 1991.

Kracauer. Siegfried, History: The Last Things Before the Last, Markus Wiener Publishers Inc., Princeton, 1995.

Linnap. Peeter, ‘Images from Borderlands’ in The Memory of Images: Baltic Photo Art Today, (ed.) Barbara Straka, exhibition catalogue, Nieswand Verlag, Stadtgaleries im Sophienhof, Kiel, March 17-April 25, 1993, pp. 44-49.

Linnap. Peeter, ‘Anthropologist Inta Ruka: 1980’s: Romantic Catalogue on Latvia’, Borderlands: Contemporary photography from the Baltic States, (ed.) Martha McCulloch, exhibition catalogue, curated by Peeter Linnap with the assistance of Valts Kleins and Gintautas Trimakas, Street Level Photography Gallery and Workshop, ‘The Cottier’, Glasgow, June 5-July 4 1993.

Meatyard. Ralph. Eugene in An American Visionary, (ed.) Barbara Tannenbaum, Akron Art Museum, Rizzoli, Ohio, 1991.

Richards. Jane, ‘Freedom Shots’, The Independent, 18.1.1994, p. 24.

Ruka. Inta, ‘My People from the Country’, Parmijas, Contemporary Art from Riga, Münster, 1992.

Ruka. Inta, People I Know, Ute Eskildsen, trans. Rolli Főlsch, Bokőrlaget Maz Strőm, Stockholm, Sweden, 2012.

Scribner, Charity Requiem for Communism, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2005.

Straka. Barbara, ‘The Memory of Images: Baltic Photo Art Today’, The Memory of Images: Baltic Photo Art Today, exhibition catalogue, Nieswand Verlag, Stadtgaleries im Sophienhof, Kiel, March 17-April 25, 1993.

Szarkowski. John, Winogrand: Figments From the Real World, The Museum of Modern Art New York, New York, 1988.

Tifentale. Alise , ‘The new wave of photography: The role of documentary photography in Latvian art scene during glasnost era’ https://www.academia.edu/1856067/The_new_wave_of_photography_The_role_of_documentary_photography_in_Latvian_art_scene_during_glasnost_era, p. 4 retrieved 14.5.2014.

Wolfe. Charles, ‘Just in Time: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and the Recovery of the Historical Subject’ in Fugitive Images: from photography to video, (ed.) Patrice Petro, Indiana University Press, Indiana, 1995.

Zipes. Jack, ‘ Something’s Missing: A Discussion between Ernst Bloch and Theodor W. Adorno on the Contradictions of Utopian Longing’, 1964 in Ernst Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature: Selected Essays, trans. Jack Zipes and Frank Mecklenburg, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1993, pp. 1-17.

Letter from Andrejs Grants to the author, 15.4.1996.

Letter from Vid Ingelvics to the author, 23.8.1996.

Artist’s (Inta Ruka) statement June 1998.

Images

Fig. 1 self-portrait of Inta Ruka, 2014 courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 2 Inta Ruka, ‘Richards Stibelis’, 2006, from Amalijas Street 5A, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 3 Inta Ruka, ‘Iveta Tavari, Edgars Tavars’, 1987, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 4 Inta Ruka, Untitled (Ruka with her models), ca.1984, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 5 Inta Ruka, ‘Agita Rutkaste’, 1984 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 6 Inta Ruka, ‘The Girl, Balvi, Latvia’, 1992 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka,

Fig. 7 Inta Ruka, ‘Emma Stebere and Jânis Stebers, Balvi, Latvia’, 1984 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 8 Inta Ruka, ‘Inese Rutkaste, Imants Rutkaste’, Balvi, Latvia’, 1985 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 9 Inta Ruka, ‘Edgars, Iveta, Daina Tavari’, Balvi, Latvia’, 1986 from My Country People, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 10 Inta Ruka, Untitled (Boy and his rabbit), ca.1984, Silver Gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Fig. 11 Inta Ruka, ‘Agita Rutkaste, Andis Rutkaste’, 1992, silver gelatin print, photograph courtesy of Inta Ruka.

Otto Umbehr, Mystery of the Street, 1928.

Otto Umbehr, Mystery of the Street, 1928.